Wrapping up the semester

After imagining the massacre and coup in Marrow, reckoning with it in Wilmington’s Lie, and finally, recovering the stories in the archive unit, I conclude with a private tour of historic sites in 1898 Wilmington. These trips are incredibly powerful: these UNCW students get to stand in the actual spaces and bear witness to what happened in this city 125 years ago. For educators outside of this port city, soon there will be virtual tours they can give their students.

We begin the tour at historic Thalian Hall at the corner of 3rd St. and Princess St. in downtown Wilmington. This theater was built by enslaved and free Blacks in 1858 and was the site of Colonel Alfred Waddell’s infamous “choke the Cape Fear with carcasses” speech merely three weeks before the massacre. Today, Thalian seats 400 people, but on October 24, 1898, more than 1000 people packed the theater to hear Waddell speak. Standing in that space, like so many of the historic locations in Wilmington, is haunting.

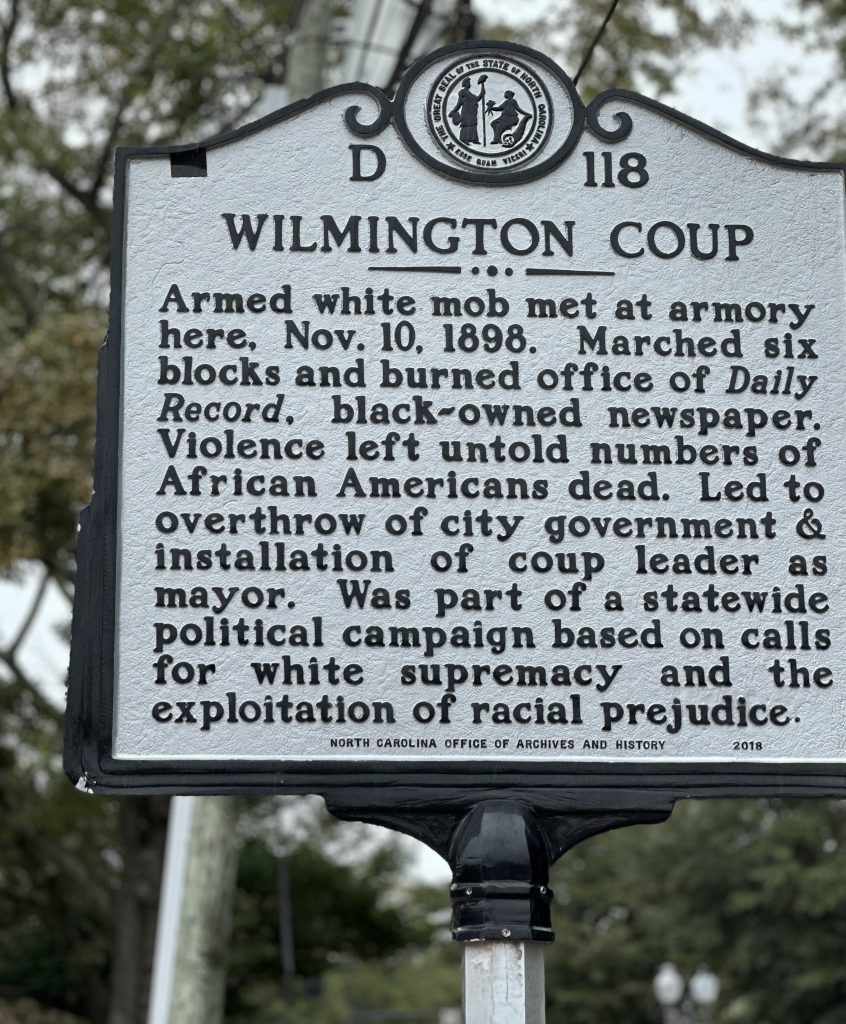

After Thalian we move a block south to Market St., where the Red Shirts began their march to Love and Charity Hall where they would destroy Alexander Manly’s printing press and set fire to the upstairs of that building. As we move east, we stop at 5th St. and read the official historical marker of the “Wilmington Coup,” which was only installed in 2018. Students invariably note that the word “massacre” is not used on the sign.

Next, we continue east for two more blocks on Market St. I note that when the Red Shirts left the armory, they were 500 strong, but by the time they turned right on 7th St. there were more than 1000 people in their ranks. And when they finally arrived at Love and Charity Hall, five blocks south of Market St., there were 1500 white supremacists ready to lynch Alexander Manly. Not finding him, they destroyed his printing press and burned the building. The most famous of photos from the 1898 Wilmington Massacre show dozens of Red Shirts proudly standing in front of the charred remains of the building, with Saint Luke AME Zion Church situated in the background. The church remains and, again, there is a palpable sense of anger and sorrow to stand in that same space. Notably, there is no historical marker in the vacant lot where Manly produced his newspaper.

However, there is a historical marker at 3rd and Church St. Erected, stolen, and re-erected in 2007, it (problematically) reads: “Alex Manly, 1866–1944, Edited black-owned Daily Record four blocks east. Mob burned his office Nov. 10, 1898, leading to ‘race riot’ & restrictions on black voting in N.C.” Here students note that the implication on the marker is that it was Manly who was responsible for the violence on November 10, 1898.

Our tour follows the route of the Red Shirts, and we move to the riverfront area of downtown Wilmington. As Zucchino and others have noted, the smoke from the fire at Love and Charity Hall, located in an African American neighborhood would have been visible to the hundreds of Black workers at James Sprunt’s Cotton Compress factory, a mile and a half away near Front St. and Walnut St. As the mob of White supremacists descended on the building, many Black laborers fled to their homes in the Brooklyn neighborhood to the northeast. Today, Sprunt’s eight factory buildings are now home to the Cotton Exchange, a shopping complex popular with Wilmington tourists. There is no historical marker that mentions its role in the 1898 massacre. There is, however, an historical marker devoted to James Sprunt, who shared in the White Supremacist mission of 1898, but also worried what the violence would do to his workforce. At the intersection of 3rd St. and Nun, his plaque, erected in 1953, reads: “James Sprunt, Author of ‘Chronicles of the Cape Fear River’ (1914), cotton merchant, philanthropist. British vice consul. His home stands two blocks west.”

now an empty lot

Our tour next moves north and east to the Brooklyn neighbor where the Red Shirts chased the scared Black citizens of Wilmington. We stop at the intersection of 4th St. and Harnett where the shooting started outside of Brunjes saloon. Today, that area is also a vacant lot that contains no historical marker. We then travel a few blocks to the intersection of 6th & Bladen, site of Manhattan Park Dance Hall, where historians speculate the bloodiest of the 1898 incidents occurred. The White supremacists fired into the club and then continued firing as terrified people fled into the streets.

The penultimate stop on our historical tour is Pine Forest Cemetery located at 16th St. and Rankin, a mile-and-a-half from Manhattan Park in Brooklyn. This African American cemetery became a tenuous place of refuge for Black citizens fleeing the violence on November 10, 1898. They hid in the forest and swamps that ring the northern border of the cemetery. An unknown number of people are thought to have died of exposure that night as temperatures dropped below freezing.

Pine Forest Cemetery contains the graves of several relatives of Charles W. Chesnutt, as well as Wilmington residents who inspired his characters in The Marrow of Tradition. The cemetery is also home to the Sadgwar family plots; Carrie Sadgwar was the wife of Alexander Manly. And Pine Forest also contains the grave of Joshua Halsey, one of the victims of 1898. Halsey’s place of rest is the first, and only, confirmed gravesite of any of the untold number of victims of the 1898 Wilmington Massacre. And it was not discovered and verified until Sullivan and Finsel did so in 2021.

We end our tour at the 1898 Wilmington Memorial, hidden in plain sight on the much-trafficked 3rd St. Students again take in the language and become upset that the descriptions of the violence and terrorism are not more explicit. This tour, much like the class itself, is an exercise in applied learning. Our goal when we stand in these spaces and bear witness to what has happened and how it’s now represented is to acknowledge the racial violence that occurred in this city 125 years ago. The tour accentuates the impact of reading The Marrow of Tradition, Wilmington’s Lie, and The Daily Record. The students have a possessive investment in these events, in these people, and in these stories.

The 1898 Wilmington Massacre forever changed Wilmington, North Carolina. This class is meant to both inform and engage UNCW students, many of whom grew up in or around Wilmington, and yet have experienced little of its history. The goal and hope, then, is that this courses not only introduces them to the historical facts of the massacre and coup, but leads them to ask difficult but necessary questions about its planning, its execution, and its aftermath, and how the racial violence of November 10, 1898 continues to shape their own existence as students at the University of North Carolina Wilmington.