by Cori Greer-Banks, Exploris School, Raleigh, NC

Making the decision to move to teach in North Carolina was a difficult one; I was born and raised in Dayton, Ohio, and I had never lived further south than Virginia Beach. If anyone knows anything about Virginia Beach, they would know the Tidewater area is not exactly known for Southern sensibilities, and neither was I. However, 2008 was a pivotal year for many in real estate – whether it was flipping homes or buying their first one – and making the trek to North Carolina was really popular. I was one of the ones casting their lot, and many friends told me that Raleigh had plenty of great schools to work in. So it was down south I went.

My undergraduate degree was in history and my graduate degree was in English Literature. To teach in North Carolina’s capital city seemed idealistic; where else could I go and teach such a dizzying array of American history and literature? This state was the first colony to declare independence from Great Britain and one of the last to secede from the Union. I would be able to learn the stories of enslaved peoples on the very plantations in which they lived, traverse the trails of the conductors of the Underground Railroad. I’d be able to immerse myself in the sounds of Nina Simone, sipping lemonade on the grounds of her birthplace in Tryon. Perhaps I could shrug off the ongoing feud of flight between my birthplace and Kitty Hawk in favor of living in a state that celebrates mountains to the sea?

July of 2008: America was in the throes of a historic election cycle and on the precipice of a deepening economic crisis. My idealistic world soon turned into stark realities. Moving south during this time period brought out the very real and deep racial divides still permeating this country, divisions many thought were behind us after the election of Barack Obama. However, a post-racial society was but a pipe dream. I would be the only black teacher in my school, and I would be one of the few black families in the neighborhood where my home was built. It was very difficult to teach middle school students about American history during this time. I remember it being one of the most isolating periods in my life. I was a young teacher, and I had no mentor to turn to ask questions about teaching difficult topics. Many of my initial experiences in North Carolina were trial and error.

I thought teaching students about the Wilmington Race Massacre would be easy, but this was a topic very few in the state knew about. It was during graduate school that I first learned of the 1898 Wilmington Race Massacre. This was back in 2007 in Professor Richards’s American Literature course at Old Dominion University. It was still called the Wilmington Race Riot and there was not the plethora of primary documents and literature we have available to us now. Our class read the novel The Marrow of Tradition by Charles Waddell Chesnutt, a fictional account of the events in Wilmington, North Carolina, and it was through this novel we learned of the only successful overthrow of a government in American History.

Written in 1901, The Marrow of Tradition was popular in Black literary circles, but it never gained full steam in the top literary echelons. Once I moved to North Carolina, I was eager to teach about this event in social studies courses. The only successful coup d’etat in American History must surely be taught in all Carolina classrooms, right?

Again, my naivety had led me astray. Very few people had even heard of a Wilmington “race riot” – or massacre – much less a coup d’etat. Native Carolinians and social studies teachers would look at me with confusion whenever I brought up the event. Maybe I was in error? Perhaps I got the state mixed up? Perhaps this event really took place in Wilmington, Delaware, and I needed to stop making myself look stupid by bringing it up to people. I went back and re-read that novel and while the fictional town was called Wellington, my college scribbled notes clearly said it was based on true events that took place in Wilmington, North Carolina in 1898.

I would not begin teaching about the Wilmington coup d’etat to middle school students until the fall of 2017, nine years after my initial move down south and at a different school where my unorthodox approaches in the classroom would be embraced and celebrated.

At The Exploris School in Raleigh, NC, where I currently teach, most had never heard of the Wilmington event, but not hearing of something has never stopped this school from tackling difficult topics before. My colleague Jessie, who was born and raised here in North Carolina, never heard of the event, and her parents (who were also born and raised here) had never heard of the event, but when I came to her with the idea to teach eighth graders about the massacre she said, “Sure; let’s try it.”

I am digressing here, but her line and the most casual way she said it during my first month at Exploris made me fall in love with the school: those four words, “Sure; let’s try it,” are indicative of the way we approach learning as a school community. Our subjects are integrated, our staff teaches collaboratively, and we are open to trying everything. In eighth grade, students do not have an English Language Arts (ELA) or a Social Studies course; instead, they take a course called Humanities. Jessie Francese, the certified ELA teacher, and I, the certified Social Studies teacher, team-teach the Common Core ELA standards through Social Studies texts. Our students read several novels throughout the year, and all of our novels focus on a different period in American history, which is the North Carolina Social Studies standard of study for eighth grade.

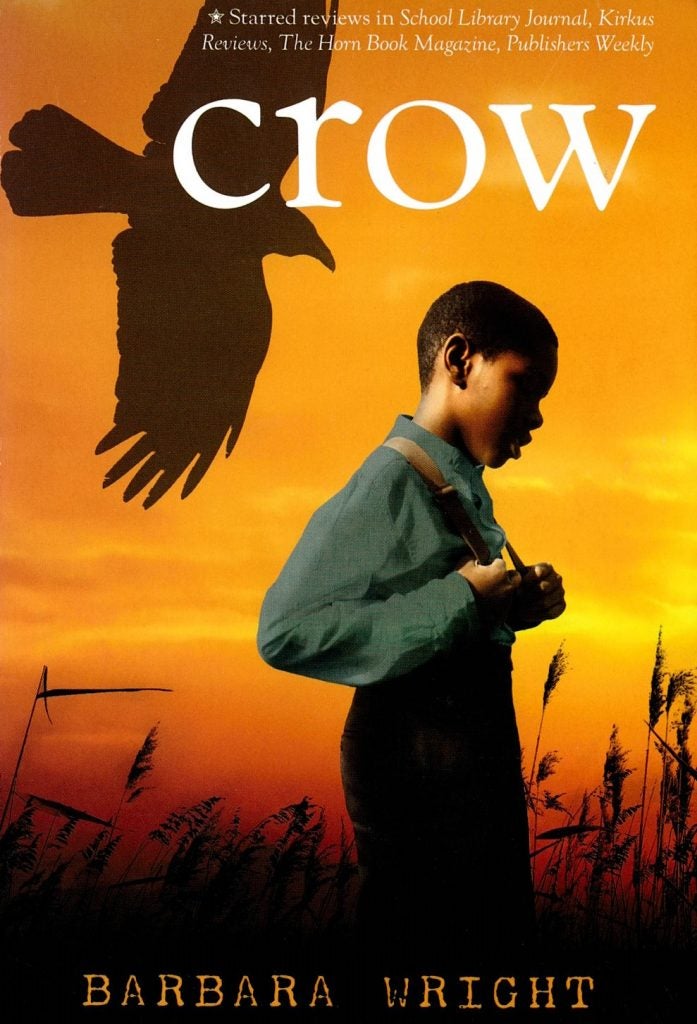

We use Barbara Wright’s YA novel, Crow, to teach adolescents about the Wilmington Race Massacre.

It is an appropriate selection; Wright approaches the event through the eyes of an eleven-year-old protagonist named Moses, but she does not shy away from the difficult parts of North Carolina’s Jim Crow period. My students learn about the burgeoning black middle class in Wilmington, the white supremacist ideas hatched in the Cape Fear Club. They read the editorial by Rebecca Felton of Georgia, who promoted the lynching of black men to protect the innocence of white women, and my students also read the response of Alexander Manly, owner of The Daily Record, who highlighted the routine rape of black women by white men throughout American history and dared to imply that some interracial relationships between black men and white women were consensual. Students analyze Alfred Moore Waddell’s “White Declaration of Independence” and imagine how members of Wilmington’s black community might respond to such rhetoric. By the time our class finishes the novel, students have a firm understanding of Reconstruction and the strategic dismantling of racial progress in the late nineteenth century. The novel humanizes the events, and my students are able to imagine a child living through a very unpredictable and scary time in the American South. This unit is courageous, bold, and caring. However, it was not enough.

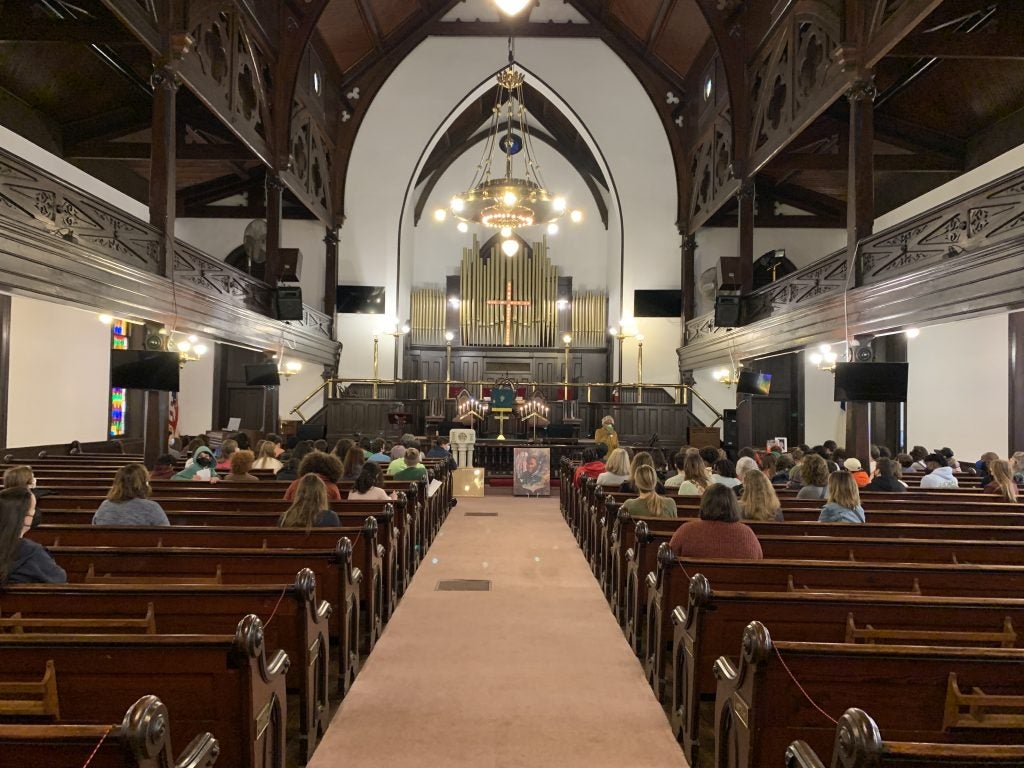

Jessie and I realized that, yes, we were doing the hard work and educating our students on the difficult history, but by and large, their parents did not know about this event. Indeed, most Raleigh citizens did not know about the Wilmington Race Massacre. So we coordinated a field experience. We drove all seventy-five of our eighth graders, a whole bunch of their parents, and the rest of the eighth-grade teaching team down to Wilmington, where we walked the path of the violence. We stopped at the Cape Fear Club, where the Secret Nine’s plan was hatched, the Sprunt Cotton Compress, where a fire broke out, and Thalian Hall Center for the Performing Arts, where Waddell riled up the white citizens of Wilmington to mob rule.

Students also visited areas of black empowerment and resistance, such as St. Stephens AME, a historic church built by both free and formerly enslaved black artisans, and Frederick C. Sadgwar, a prominent black carpenter and architect in the post-war South. Prior to our trip, our students had explored the economic and social opportunities for African Americans in post-Civil War Wilmington. And then, right there in twenty-first-century Wilmington, our students turned towards their parents and taught it to them.

This kind of experience is what gets me really excited: seeing the fruits of our efforts in the classroom blossom right there on the streets of Wilmington. It makes me view our classroom lessons as an act of justice and of unveiling what has been kept secret.

Cori Greer-Banks teaches 8th-grade Humanities at The Exploris School in Raleigh, NC, and previously taught at the Ramstein American High School in Germany. She holds a BA in History from the University of Maryland and an MA in English from Old Dominion University.