A University Classroom Writing Project

By Shelley Ingram, Associate Professor of English, University of Louisiana at Lafayette

“I only have this left to say: the world is worse off without Randall Kenan in it.”—Omari Weekes

Randall Kenan’s stories of Black queer southern life have had an immense impact on Southern letters and Southern writers. I teach a Kenan short story almost every semester, whether it’s “The Origin of Whales” in a foodways course, “Tell Me, Tell Me” in a class on ghost lore, or “What Are Days?” in a unit on the demon lover trope. Few to none of my students will have heard of, much less read, Kenan, but his work is, they attest after their first encounter, a marvel. So when I had the opportunity to propose a topic for an upper-level single-author course at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette in the summer of 2022, I took a chance and proposed a course on Kenan. After a meeting of the committee that decides such things for my department, I received a text message from a colleague. “I was thrilled to see your proposal,” he wrote. “I was once a student of Randall’s, and he was a wonderful teacher and human.”

When Kenan died unexpectedly in 2020, the outpouring of grief by writers, readers, former students, and friends – on social media and in more formal venues – made it clear how much he meant to those who knew him, both by his words and in his life. I thus decided to focus the course primarily on the intersections of grief and death, place and difference, and communal knowledge, particularly as they were navigated in his fiction by marginalized communities. During the semester we read Kenan’s novel A Visitation of Spirits (1989), his two short story collections, Let the Dead Bury Their Dead (1993) and If I Had Two Wings (2020), a few of his lectures and essays, and critical analyses of his fiction. And while our primary themes were these intersections of grief/death/memory, the interweaving of place and difference, and the holding of communal folk knowledge, our discussions certainly wandered into other fields.

It was an eight-week, asynchronous online summer class with a relatively small enrollment – only ten students, mostly senior English majors and graduate students. I designed the syllabus so that we began at the end, in a way, with published remembrances of Kenan and the communal mourning of his passing. This decision had a real impact on how students approached his work and interpreted his fiction. They first and foremost were looking for him, for the man who had left such an impact on those who knew him. The students were exceedingly kind, almost affectionate, in their reading of his fiction, and they paid very close attention to moments that spoke of hurt and grief and oppression. I do not know if I would teach the course this way again, but at that specific time, with Kenan’s recent death and the pain and grief we had collectively experienced through the upheaval of the previous years, it was hard to think of the course in any other way.

As in all of my upper-level literature courses, I have five primary skills I design my assessments around: active reading, argumentation, communication, ownership of ideas, and collaboration. It was the last skill, collaboration, that I felt would suffer the most in an asynchronous online course. So much of Kenan’s writing is predicated on the idea of community that I was afraid the students’ relative isolation would negatively impact their engagement with his work, that they would miss the opportunity to experience his fiction as part of a community of readers. I thus decided to make three of their five primary assessments collaborative. The first of these collaborative assignments was a group chat, using an app all students had access to. The chat was informal and was not limited to a discussion of the readings. The second was a group annotation of secondary readings using Hypothesis®, a tool available through our learning management system. The final collaborative assessment was the group reading notes. I provided a link each week to a Google document and required students to make at least five reading notes per week. It was in this space that the real work of the course happened.

The students produced over eighty single-space pages of notes, conversation, analysis, and insight. At sixty thousand words, they had written a book. And because our class read all of A Visitation of Spirits, Let the Dead Bury their Dead, and If I Had Two Wings, they were often writing about stories that have been slighted or ignored by other literary critics. With the students’ permission, we share here excerpts from that document. I and the graduate students in the course – Kyrsten Householder, Oakley Montgomery, and Cheylon Woods – have chosen portions that we feel exemplify the conversations that were happening, present particularly insightful and significant readings of familiar texts, or focus on Kenan’s new and lesser-known stories. While there was a lot of conversation about, for example, “Clarence and the Dead” and “Foundations of the Earth,” we have limited the amount of space we give to those discussions as those stories are already so often taught, and we wanted to inspire our readers to add other works to their repertoire.

The notes themselves are edited for length, clarity, spelling, and occasionally style, and the students identified by name in the document have all given permission for their names to appear. Each week begins with a list of readings, followed by a portion of that week’s notes with short descriptive headings signaling the primary topics of that section. Included is the course syllabus, with the course’s student learning outcomes, weekly readings, assignments, and journal prompts.

The group reading notes, I believe, present a rich resource for anyone teaching the fiction of Randall Kenan and a look at how readers encounter Kenan for the first time. I hope that I have done justice not only to the work of Kenan as a writer and teacher, but also to the students at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette who so fully immersed themselves in his world.

One thing that continues to surprise me about this course, months after it has ended, is that I often forget it was online and asynchronous, that we didn’t meet in the space (virtual or otherwise) of a classroom. The students wrote a lot of words in a short amount of time, between the group chats, journal entries, essay annotations and, of course, the group notes. We got to know each other’s (writing) voices well, and the continual interaction between us all meant that it was the best approximation of an in-person discussion class I have been able to hold online. That much writing – and that much reading of others’ writing – really did forge a community in the sometimes-sterile space of online learning. It was also an interesting experience to center Kenan as a person, which, as I said above, did affect how students read the texts. I am not sure I would take this exact approach again because it tended to shift focus away from his texts as texts. Kenan was a formal innovator who never played it safe in terms of style and structure. And while we did have meaningful discussions about form – for example, the insertion of dramatic dialogue in A Visitation of Spirits – those discussions were rarely initiated by the students. But students weren’t simply substituting a biographical approach. Instead, their focus trended toward the representation of humanity in his fiction, and on Kenan’s complex figurations of good and bad, innocent and guilty, human and non-human. By approaching his fiction with kindness and empathy, engendered by their readings of the memorials to Kenan, students were able to meet many of the goals of humanistic enquiry: a better understanding of people and their places, including their grief, their mourning, their joy, and their community.

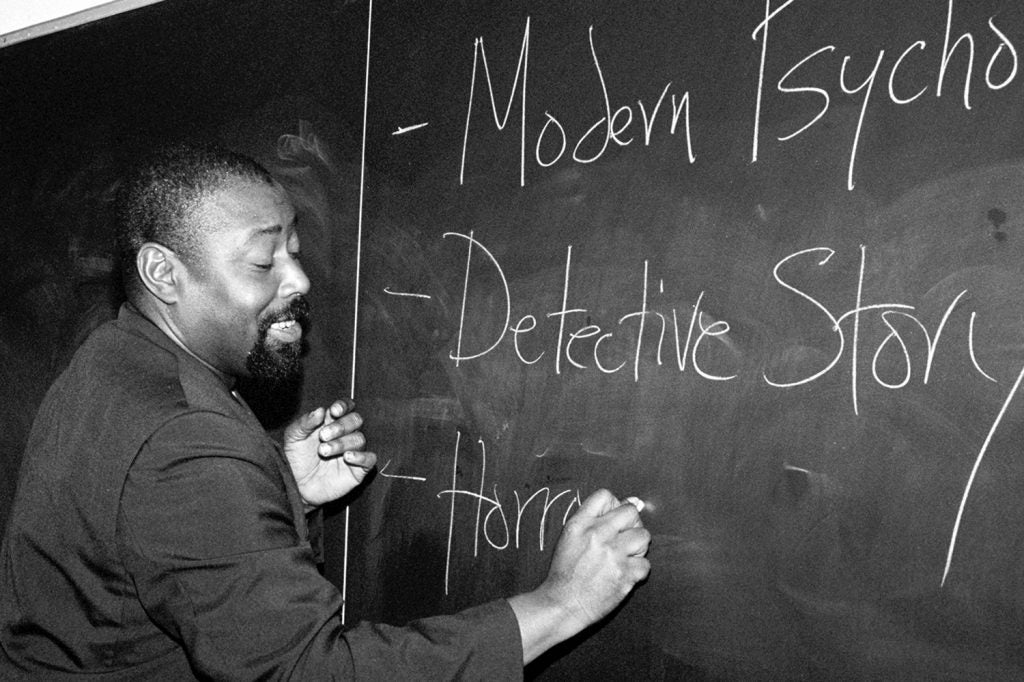

The photographs above are from Sheryl Cornett’s interview essay on Kenan in NCLR 2006.

Shelley Ingram is an Associate Professor of English at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette. Her research focuses primarily on the relationship between folklore and literature, including its connections to ethnography and race, folk narrative, food, and environment. She has written on the literature of Randall Kenan, Shirley Jackson, Lee Smith, and Jesmyn Ward, among others, with essays appearing in edited collections and in journals such as African American Review, Food & Foodways, and Southern Quarterly. She is coauthor of Implied Nowhere: Absence in Folklore Studies (Oxford University Press, 2019) and editor of Wait Five Minutes: Weatherlore in the Twenty-First Century (University Press of Mississippi, 2023).