Wilmington’s Lie: Historical and Cultural Analysis

Chesnutt’s The Marrow of Tradition allows the students to get to know the characters of the 1898 Wilmington Massacre, even if they were fictional residents of Wellington. David Zucchino’s Wilmington’s Lie makes the events at the end of the nineteenth century all too real and lasting. There is an immediacy that reaches the students, and I believe that urgency is heightened because Chesnutt’s novel allowed them to feel like they knew these people’s interior lives.

David Zucchino won the 2021 Pulitzer Prize in nonfiction for his history of the build-up, execution, and aftermath of the 1898 Wilmington Massacre. The text is comprehensive and eminently useful. But it’s important to note that Zucchino’s work builds on the long history of scholars before him – many of them African American. In addition to Chesnutt’s fictional account, David Bryant Fulton, who wrote under the pseudonym Jack Thorne, also composed an early, lightly fictionalized story: Hanover; Or, The Persecution of the Lowly (1901). Helen Edmunds’s doctoral thesis The Negro and Fusion Politics in North Carolina, 1894-1901 was published in 1951. H. Leon Prather’s essential history, We Have Taken a City: The Wilmington Racial Massacre and Coup of 1898, was first published in 1984. David Cecelski and Timothy Tyson’s edited collection, Democracy Betrayed: The Wilmington Race Riot of 1898 and Its Legacy, was published on the hundred-year anniversary of the massacre. A decade later, the Wilmington Race Riot Commission released a book written by researcher LeRae Umfleet titled, A Day of Blood: The 1898 Wilmington Race Riot, which was based on the 2006 Commission Report. Finally, Sullivan’s and Finsel’s work is an additional invaluable resource. Zucchino’s book includes original research, but also builds upon the work of these scholars and writers.

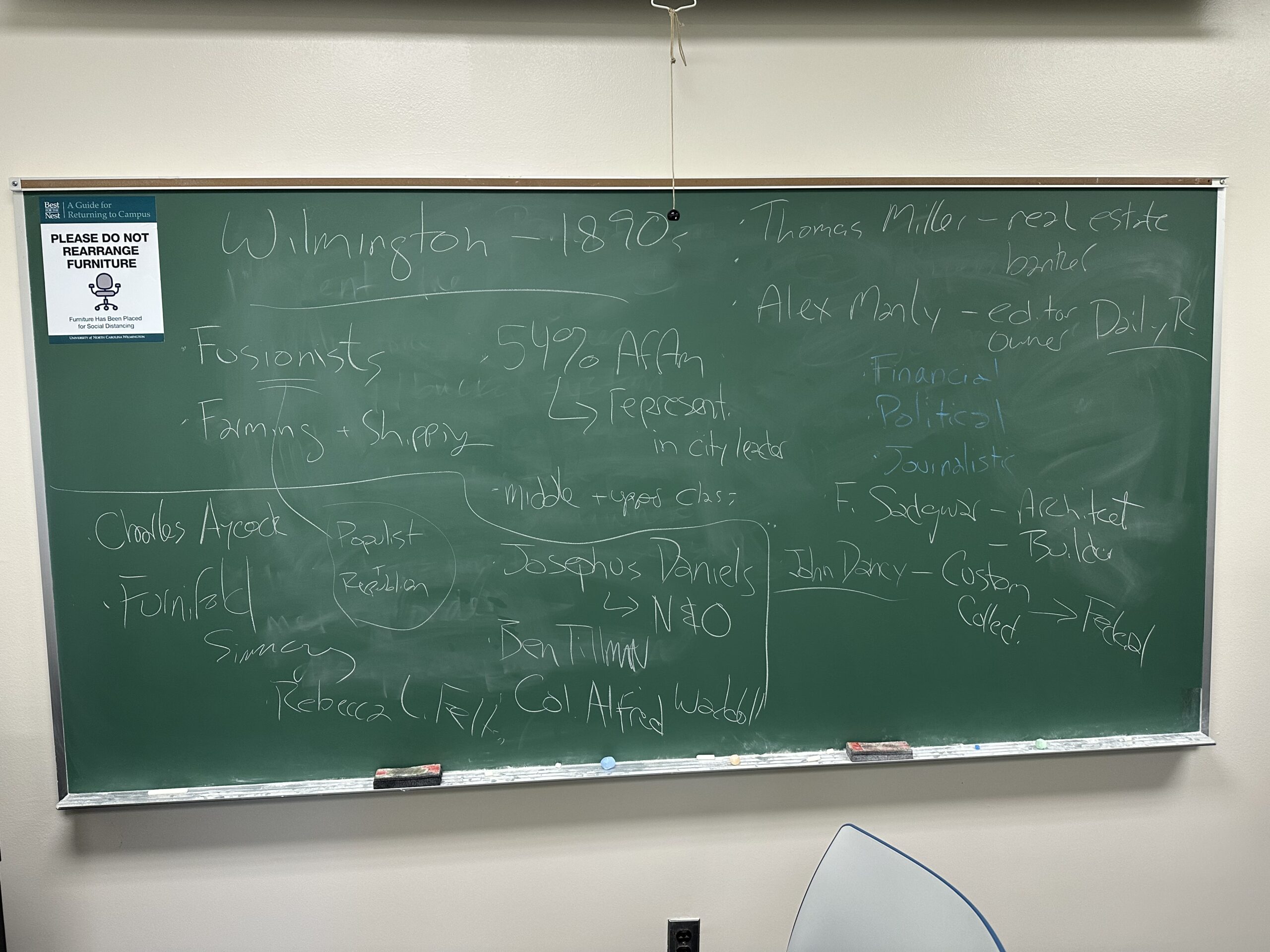

Wilmington’s Lie contextualizes the 1898 massacre and coup for the students. They learn the history of the city and the social and political forces that coalesced after the Civil War to produce the largest city in the state of North Carolina by 1898, a city that was 56% African American and had a multiracial city government and police force. As the students also learn, it’s the only city in the history of the US to be taken over by a militant coup. The added benefit of using Wilmington’s Lie is that Zucchino follows the historical arc of the city after the massacre and coup. These chapters are particularly shocking to students. They learn the lasting effects of Jim Crow, the Grandfather Clause (e.g., there were 126,000 registered Black voters in North Carolina in 1896; by 1902 that number had dropped to 6100), and the perpetual threat of racial violence (e.g., the percentage of Black residents in Wilmington has dropped from 56% in 1898 to 17% today).

We use the Bedford Cultural Edition of The Marrow of Tradition in our class because it contains a wealth of primary, nonfiction essays from the time that help contextualize and augment Zucchino’s book. These sources include:

- Thomas E. Watson, “The Negro Question in the South” (1892)

- Ida B. Wells, Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases (1892)

- Fannie B. Williams, “The Intellectual Progress of the Colored Women of the United States since the Emancipation Proclamation” (1893)

- Booker T. Washington, “The Atlanta Exposition Address” (1895)

- Plessy v. Ferguson & Dissent (1896)

- W.E.B. DuBois, The Conservation of the Races (1897)

- Rebecca Latimer Felton, Letter to Atlanta Constitution (1897)

- Alexander Manly, Wilmington Daily Record, Editorial Response to Felton (1898)

- Anonymous Letter to William McKinley (1898)

- Jane Murphy Cronly, “An Account of the Race Riot in Wilmington, N.C. in 1898” (1898)

The Watson text introduces students to the larger context of race relations in the United States in the last decade of the nineteenth century. The excerpt from Wells’s book makes all too real and revolting the realities of lynching in the United States. The conversations about Sandy’s impending lynching in The Marrow of Tradition become much graver considering Wells’s accounts (and the accompanying photographs in the book). Williams’s piece continues our conversation about the relationship between gender and race in the novel and in real life. Washington and DuBois create a space to discuss the most effective philosophies of racial uplift and success. Upon reading these two pieces, students immediately connect Chesnutt’s Dr. Miller with Washington, which often leaves them conflicted because they often prefer DuBois’s approach but felt that Miller was a tragic hero in the novel. Reading Plessy and the dissenting opinion by Justice John Marshall Harlan gives the students a feel for how the legal system went out of its way to justify a practice so unjust for African Americans. The Felton speech and Manly’s response are also included in Zucchino’s text, but students get to isolate the two here, noting especially the year difference between Felton’s speech and its republication in North Carolina newspapers. We also note that Manly’s editorial response in the August 18, 1898 issue of the Daily Record is only available through its republication (and likely embellishment) in other papers. The Third Person Project has a physical and digitized copy of that issue of the Daily Record, but its contents are blurred beyond recognition. This issue is taken up in the third unit of this course. Finally, the Cronly diary entry and the letter to President McKinley (also in Zucchino) illustrate that there were White allies in Wilmington during the massacre, but those allegiances stopped at the White House, where McKinley presided thanks, in part, to the votes of thousands of African American voters.