by Guest Feature Editor Casey Kayser

When Editor Margaret Bauer first asked me to guest edit a special feature section of the North Carolina Literary Review on disability in North Carolina literature, I was thrilled about the opportunity. In fact, a friend and colleague of mine from graduate school at Louisiana State University, Kirstin Squint, had recently served as the first guest editor for the 2023 special feature section. I was happy to join the ranks of my esteemed colleague with this honor, but to echo Kirstin’s words in her last blog, I did not know what I was getting into in terms of the work it would entail!

From the initial drafting of the CFP to finalizing content, the entire process has been an immense amount of work but rewarding all along the way. Such rewards have included discovering and revisiting North Carolina writers and literary texts that I love, and learning from the contributors that I worked with, as well as those writers and artists whose work is featured in the issues. Perhaps the greatest reward has been learning from writers and artists with disabilities about their experiences and having the opportunity to honor their voices.

One of my favorite parts of the process was getting to meet several of the authors I worked with at the South Atlantic Modern Language Association conference in November 2023 in Atlanta. I assembled a panel to publicize some of the great work that would be appearing in the 2024 issues, such as Delia Steverson’s wonderful essay on Mary Herring Wright (1924-2018), a Black and Deaf writer and teacher who wrote two memoirs about her life experiences. The two works span from her childhood and education at The North Carolina State School for the Blind and Deaf as an adolescent in the Jim Crow South to her experiences in adulthood post World War II. It was very interesting for me to learn about Wright’s life and the racial and other dynamics that shaped deaf education in the early twentieth century.

Also taking part in the SAMLA panel were Paula Eckard and Donna Summerlin, who each presented their fantastic essays on Lee Smith’s work. Smith has always been one of my favorite North Carolina writers, but I had not read her book On Agate Hill (2006) for many years and had not yet read Guests on Earth (2013) until working with Donna on her essay. I didn’t know a lot about the history of Highland Hospital and the tragic 1948 fire that took the lives of Zelda Fitzgerald and eight other women, a topic of Donna’s essay, which focuses on mental health and the institutionalization of women during that time period. Paula’s essay gave me the opportunity to re-read On Agate Hill and her thoughtful analysis of disability, war, and motherhood in the book led me to think more deeply about that text.

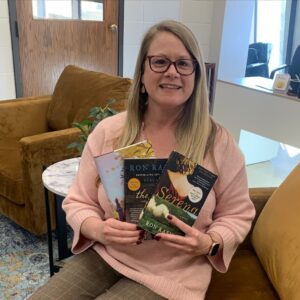

Taylor Hagood’s essay on Ron Rash’s Serena (2008) not only taught me about the historical practice of Mensur fencing in early twentieth century Germany but introduced me to a writer I had always meant to read but hadn’t gotten around to yet. Suddenly, I was obsessed! I watched the film the same day I finished the book (spoiler: not as good as the book!) and then went on to read nearly all Rash’s other novels.

Because of my editorial work, I came to my Spring graduate seminar on Gender, Literature, and Medicine with enriched knowledge and a renewed enthusiasm for the disability section of the course. In addition to teaching several pieces by disability theorists and narratives by writers with disabilities, I read for the first time and then taught Geek Love (1989) by Katherine Dunn, a book Taylor and I had discussed during the editing process. While Geek Love has been both celebrated and critiqued by disability studies theorists, it nonetheless cultivates dialogue on issues such as the abnormal/normal binary, the medicalization of disabled bodies, and the use of disability as a narrative device.

Ultimately, the greatest reward throughout this process has been learning from artists and writers about their personal experiences with disability. Just to offer a few examples, Donna Stubbs’ mixed media piece Eigengrau (German for intrinsic grey, dark light, or brain grey, the color that many people report seeing in the absence of light) helped me to visualize the color Stubbs perceives in the lower half of her right eye due to an optic nerve stroke she suffered several years ago. And I was very moved by the experiences James Tate Hill writes about in his memoir Blind Mans’s Bluff (2021). The print issue includes an interview with Hill, a writer who was diagnosed with Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy at the age of 16, a condition that rendered him legally blind. His book outlines his journey from hiding his blindness from family and friends for 15 years to finally disclosing it and reaching acceptance. It has been an honor to learn about and highlight the range and diversity of disability experiences and voices, and hopefully, help raise awareness and cultivate deeper understanding.

And from Margaret I learned about the commitment and labor it takes to manage and publish a unique and renowned journal like NCLR! Although I have glimpsed only a fraction of the work she and her staff take on each day, I am incredibly impressed by what they do and in awe of Margaret’s dedication to this journal for the past 27 years. And thank you for this opportunity, Margaret—I’m grateful to now have experience in a guest editor role! I also want to thank Kirstin for her guidance and advice.

You can check out the Winter and Spring 2024 online issues on NCLR’s website and we encourage you to subscribe today to reserve your copy of the forthcoming print issue!