Friday from the Archives: “Resisting Being Written Out of History: Women Activists and Recorders of the 1929 Gastonia Strike” by Walter Squire from NCLR 9 (2000)

Factory workers striking. Children caring for themselves while parents work. Home birth control before and after pregnancy. Families moving to cities on the promise of better education and livelihoods.

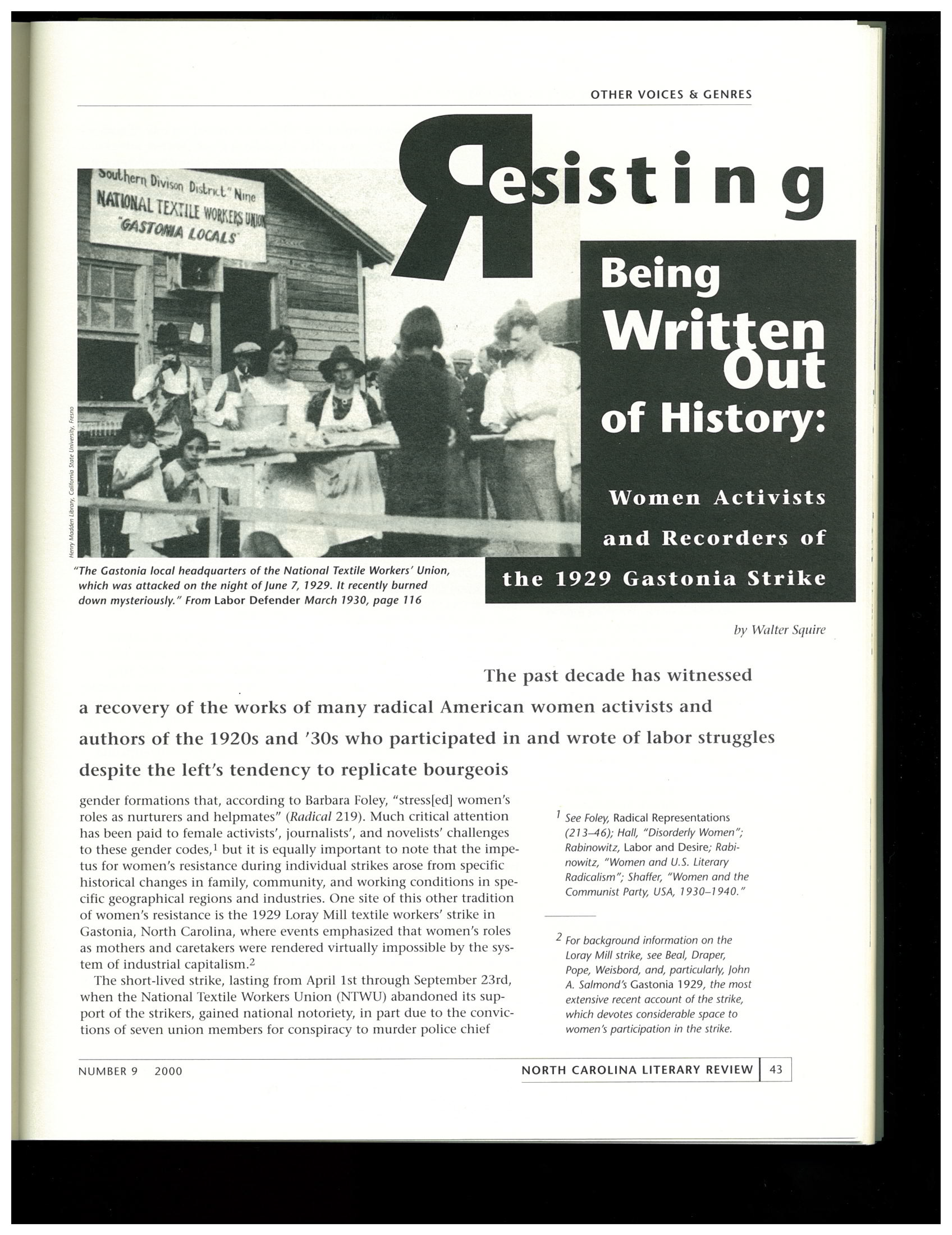

In the mid 1920s, many widowed women moved their families away from the farmland of North Carolina to find work for themselves and education for their kids in the factory towns like Gastonia. Promises broken, the millworkers went on strike in 1929, led primarily by women in the community.

Squire’s essay looks at three novels, not at all loosely based on the 1929 Gastonia Strike: Fielding Burke’s Call Home the Heart, Grace Lumpkin’s To Make My Bread, and Dorothy Myra Page’s Gathering Storm. What we might now call community action is maybe the centerpiece of these stories. Squire writes:

“Significant changes in sexuality and community attempted to compensate for these strains upon women. Hall and her colleagues found ample evidence that women practiced birth control and, to a lesser degree, that women taught one another how to self-induce abortions (Hall, et al. 159). Hall further explains that women also developed networks of assistance, child care, information transference, and community policing. When children were born, mothers were presented with used clothing and other gifts; children were raised not solely by their mothers but also by female relatives and neighbors; “poundings” (the collection and distribution of food) were organized when members of mill village families became ill, and women took turns staying up and nursing ailing members of the community; women regularly visited one another to discuss events transpiring in their communities and to assess community members’ needs; and women policed communities, ensuring that children did not skip school, monitoring the courting and sexual habits of young adults, and working with mill owners to coerce men away from the “rough life” of drinking and fighting and to make them “settled, dependable breadwinners” (Hall, et al. 172).”

He then continues through the essay to show examples of each area within the novels, as well as detailing the actual events portrayed in the fictional stories.

Learning from and about the past is one of the hallmarks of literature and increased literacy. May we continue the fight for access to our history and continue making the world a safe, equitable place for all.

Read the entire essay on GaleCengage or purchase a copy of the 2000 issue.