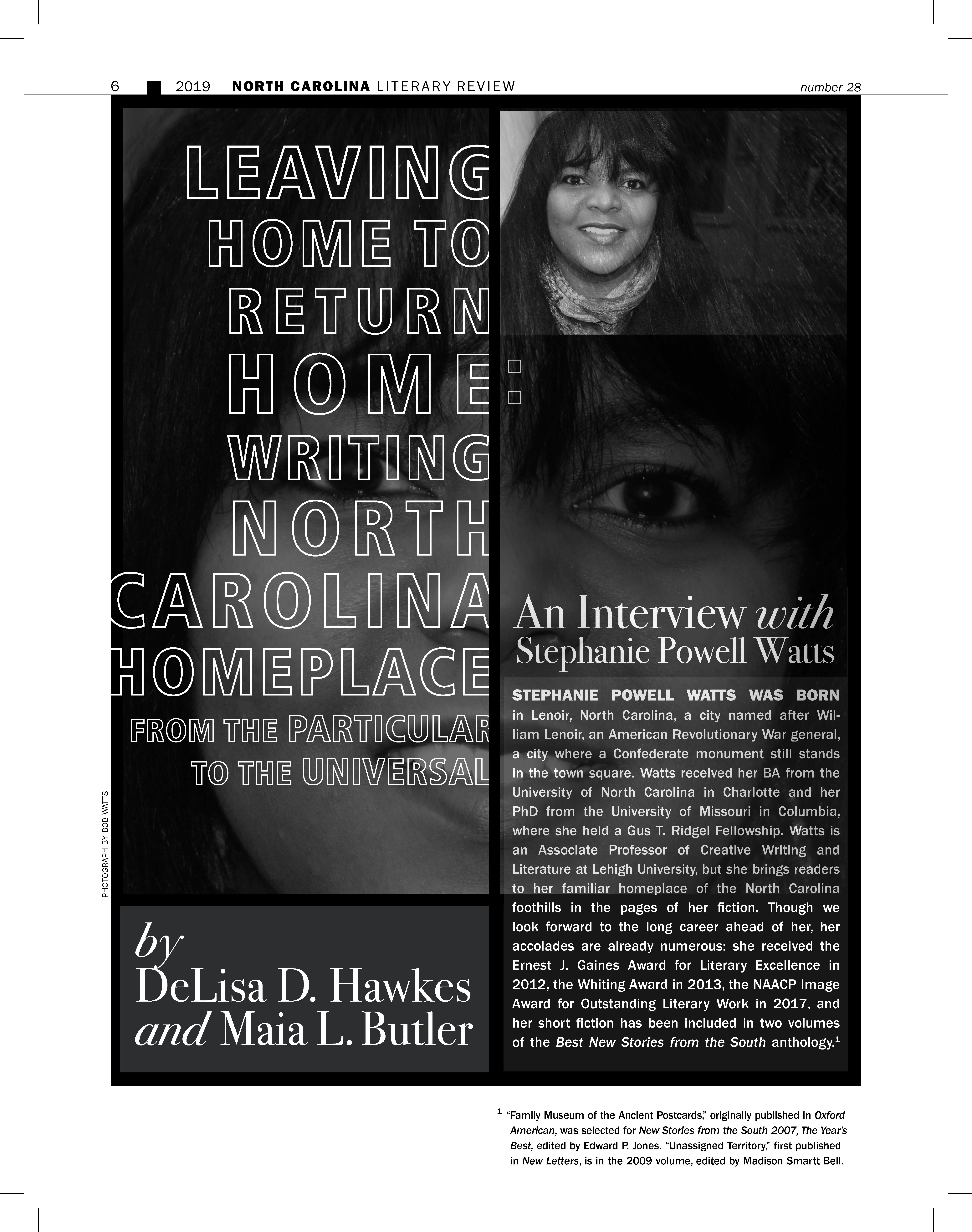

Friday from the Archives: “Leaving Home to Return Home: Writing North Carolina Homeplace from

the Particular to the Universal, an Interview with Stephanie Powell Watts” by DeLisa D. Hawkes and Maia L. Butler in NCLR 28 (2019)

In their interview, Hawkes and Butler wrote, “Grounded firmly in a long tradition of North Carolina literature, Watts situates her works at the nexus of strong traditions in Southern literature, African American literature, and women’s literature. No One is Coming to Save Us is a novel thick with representations of place, space, and home. Watts’s African American characters long for those spaces where they can feel at home, both in their changing community – rapidly changing in some ways, slowly in others – and in their distinct North Carolina foothills region within the broader South.” The entire interview goes into Watts writing practices, novel inspirations, and personal views of “back home.”

Do you feel that generational differences and experiences figure in the novel? I’m thinking especially considering depictions of black womanhood, maybe a little bit with Ava and her online community. What do you think about the generational differences between Sylvia and her sister?

Watts: This is something that I find incredibly interesting. You think about the changes that have happened, especially in African American life, in the last fifty years, and they have been monumental. There are some things that have not changed; racism as we know is alive and well. It’s just amazing; there are people who are alive who remember not being able to go into a restaurant – my father and mother are some of them – who remember having to go to the back of the bus. In South Carolina, my mother said, they would have to walk on a different side of the street if white people were walking on the street. They remember this, this is in their lived experience.

My mother isn’t very old, but my mother’s life and my life are very different. I remember one time I was talking about being in the locker room with my schoolmates, and she was asking me about them. Most of them were white, and she was asking me about their habits, what they did, like it was some kind of sociological research or something. It dawned on me that she had never been to school with white people.

So there are some real differences. Some of the advice that I would hear from the past generation just felt so weird. And I don’t mean that it wasn’t true, or it wasn’t sound. It just felt weird. Like, “Don’t trust white people; they will always let you down. If they had to choose between other white people and you, they will always choose other white people.” Those kinds of things. Is that true with everybody? It was one hundred percent true for their generation, I can’t deny that, and that is real. But then having to figure out how we talk across generations. If someone were looking at my mother or someone of her generation in a store, that person is definitely trying to find out if she’s a thief. I don’t know in my generation.

There are all these kinds of questions that are fascinating to me. How much can you take from a previous generation, and how much do you have to reinterpret and move into another space? There was a time in human experience where you figured, I’m going to live just like my parents lived, I’m going to live just like my grandparents lived. But somewhere along the line that changed. Now you don’t necessarily live in one little area. There was a time when, if you moved, you might never see these people again, or you might see them every couple of years. That sort of way of life, because of technological advances, it’s just changed. Those are the things that are just rolling around in my head, that I find so interesting. I want to figure out how to get my characters to work through some of those issues.

Read the interview on ProQuest or order the NCLR 2019 issue.